The Coastal Issues Story

1. Climate change and sea-level rising

Sea-levels have been rising for hundreds of years, and there are concerns that the rate of sea-level rise will accelerate. This could lead to widespread flooding of low-lying areas affecting millions of people worldwide and high costs of economic damage, if adaptation does not take place.

From 1901 to 2010, global mean sea-levels rose by 1.7±0.2 mm/yr, and from 1993 to 2010, rates of 2.3±0.4mm/yr were recorded (Church et al. 2013). Sea-levels do not respond instantaneously to a rise in temperature as oceans and ice sheets take a long time to respond. Therefore there is a time-lag between atmospheric warming and sea-level rise, known as the commitment to sea-level rise.

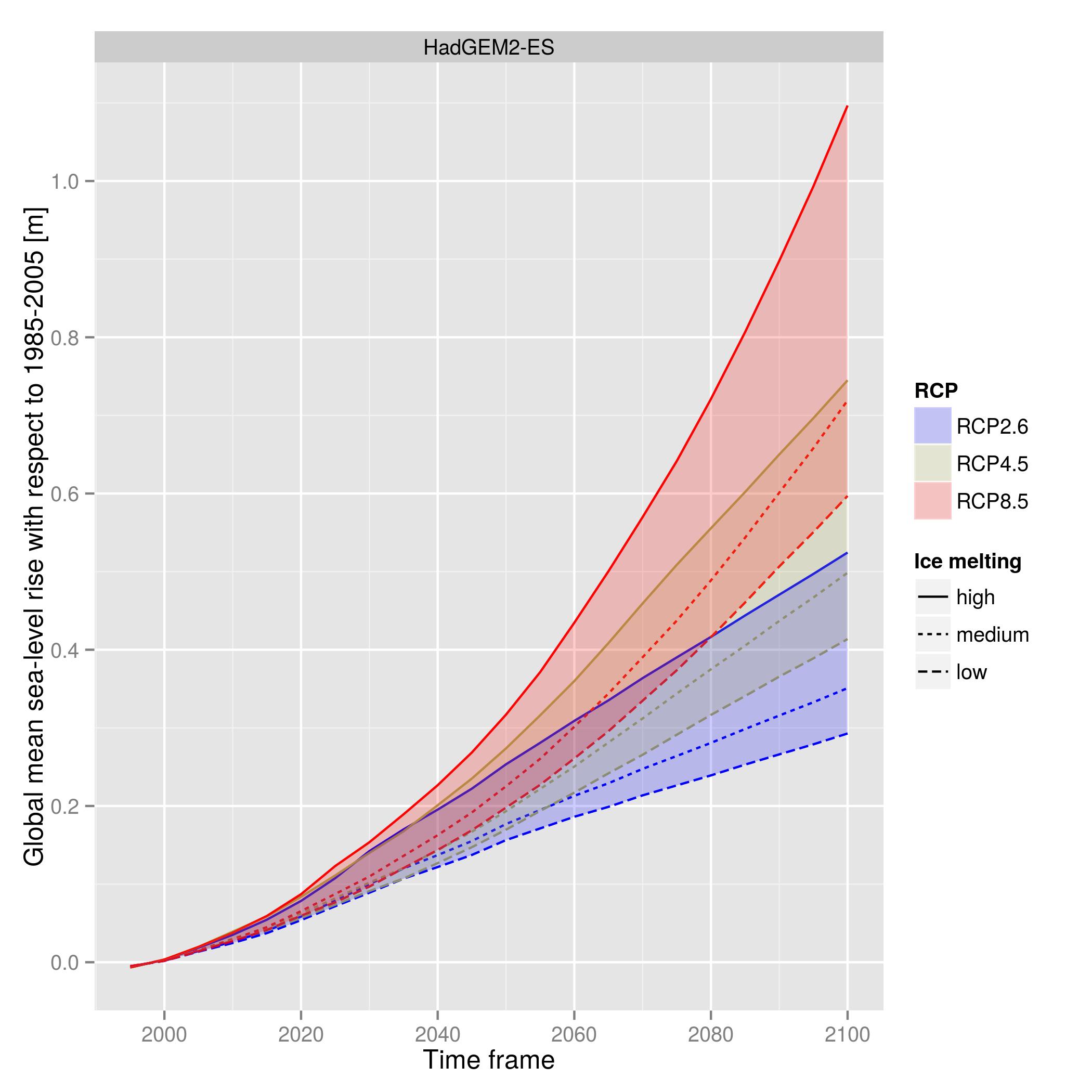

Future projections of sea-level rise vary according to a range of scenarios, called Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). Projections from three scenarios (named RCP2.6 representing a world of climate mitigation, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 representing a world of much higher emissions) is shown based on model projections from HadGEM2-ES. Each scenario indicates a family of projections based on the uncertainty associated with the rate of ice melt that contributes to sea-level rise.

2. Consequences of sea-level rise

By the 2080s, global mean sea-levels (assuming a median rate of ice melt) are projected as 0.31m (for a 2.0°C increase in temperatures since pre-industrial), 0.35m (for a 3.2°C increase in temperatures since pre-industrial) and 0.57m (for a 5.2°C increase in temperatures since pre-industrial). The commitment to sea-level rise means that even if global mean temperatures stabilise, sea-levels will keep on rising for many decades. Without stringent mitigation, sea-levels are expected to continue to rise into the 22nd century.

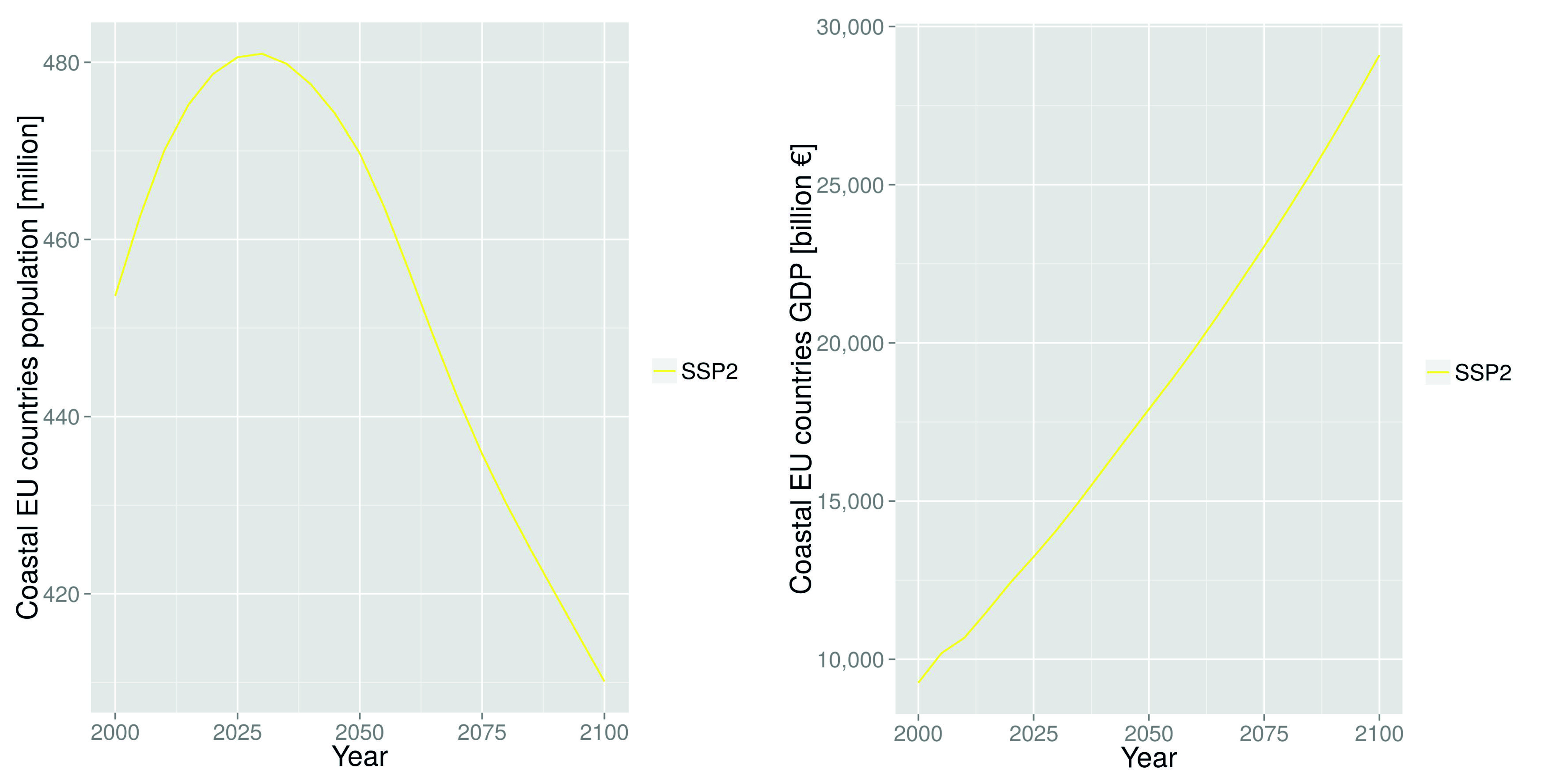

Socio-economic conditions will be affected by sea-level rise. The costs and impacts presented here follow a Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2 ‘middle of the road’ scenario: There is some progress towards development goals, but there is still a dependence on fossil fuels. In the EU throughout the 21st century, population decreases, but wealth increases (O’Neill et al. 2014).

The atlas shows potential costs of sea-level rise for flooding and adaptation for EU countries, and people exposed in port cities with a population of greater than 1 million people around the world.

References:

Church, J. A., Clark, P.U., Cazenave, A., Gregory, J. M. Jevrejeva, S. Levermann, A. Merrifield, M.A., Milne, G.A. Nerem, R.S. Nunn, P.D. Payne, A.J. Pfeffer, W.T. Stammer, D. and Unnikrishnan, A.S. 2013. Sea Level Change. In: Working Group I Contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (AR5).Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis.

Hinkel, J., Lincke, D., Vafeidis, A.T. Perrette, M., Nicholls, R.J., Tol, R.S.J., Marezion, B., Fettweis, X., Ionescu, C. and Levermann, A., 2014. Impact of future sea-level rise on global risk of coastal floods. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111, (9), 3292-3297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222469111

O’Neill, B.C., Kriegler, E., Riahi, K., Ebi, K.L., Hallegatte, S., Carter, T.R., Mathur, R.,& van Vuuren, D.P. 2014. A new scenario framework for climate change research: the concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change, 122, (3), 387-400.