Social Change and Sea-Level Rise in the Maldives

1. An atoll island chain situated in the middle of the Indian Ocean

Small, low-lying islands have been seen as highly vulnerable to sea-level rise since the issue of climate-induced sea-level rise was raised in the 1980s. Regional assessments have highlighted potential impacts, including salinisation, flood damage to agricultural land and buildings, and in the worst case forced migration.

The Maldives are an atoll island chain situated in the middle of the India Ocean. The 1,192 islands are very low-lying with a maximum elevation of 2.4m above mean sea-level, and are at risk from rising sea-levels. The nation is also undergoing much social change as policies of population concentration means there are high rates of urbanisation and migration to the capital city, Malé. Today, Malé houses around one third of the national population of 300,000 people on just 2.3km2 of land, making it one of the most densely populated cities in the world.

2. Creation of a new island

To overcome population pressure, a new island was created by dredging sand and claiming land from the sea. Construction finished on the new island, Hulhumalé in 2002 and it is now home to over 20,000 people. With some knowledge of sea-level rise, engineers raised the island to 2m above mean sea-level. But with greater scientific knowledge and improved projections since the island was designed, is the island high enough to withstand extreme events?

3. Consequence of climate change: Impacts of sea-level rise

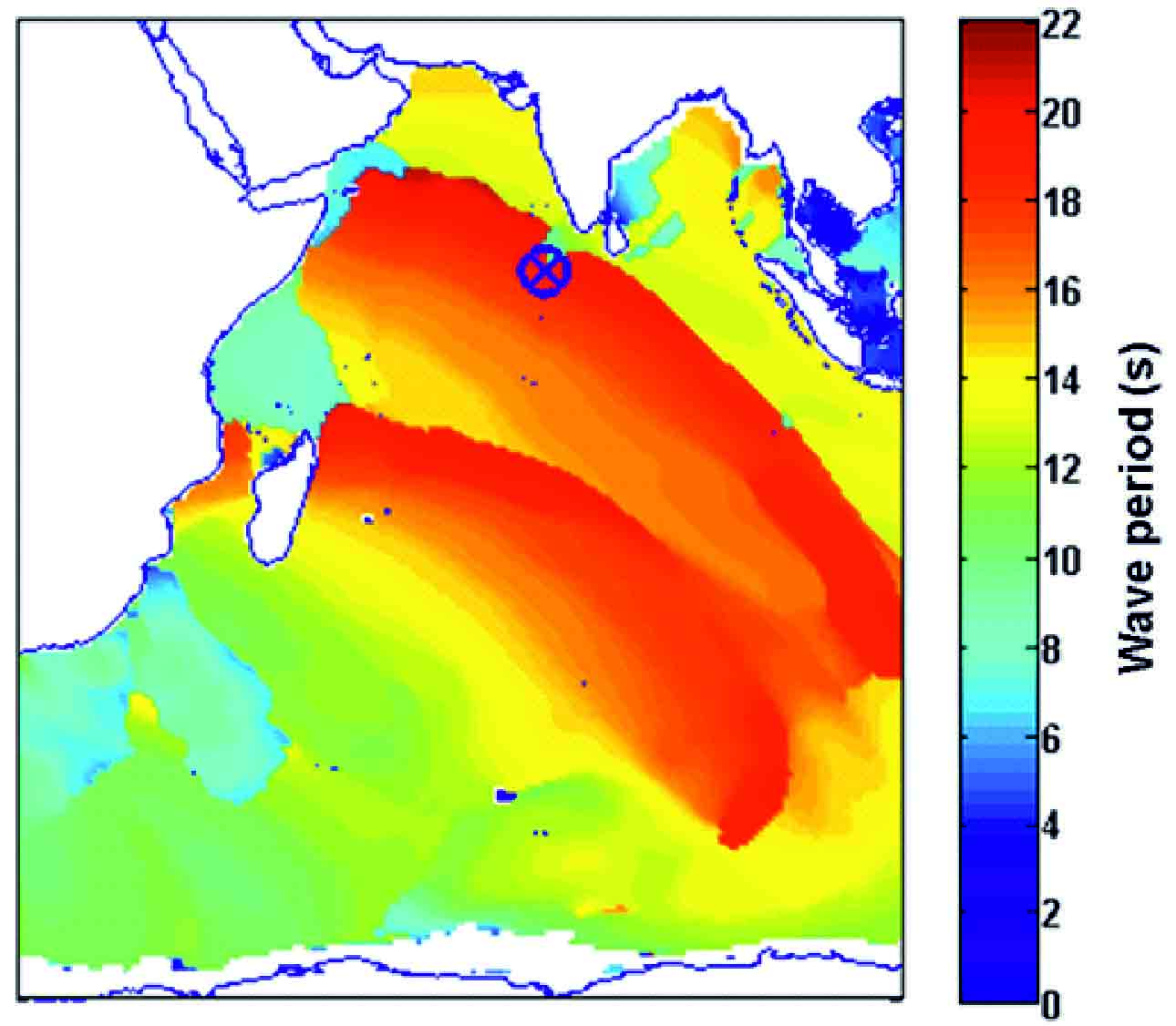

Using tide gauge records, mean sea-level rise from 1989 to 2014 was recorded at 4.4±0.2mm/yr. An assessment of past wave conditions, indicated long-period swell waves generated in the Southern Ocean resulted in flooding on natural islands, often over a period of several days in May 2007. The figure illustrates hindcast wave periods which project past conditions. It suggests that two swell wave events occurred, which matches some observations.

With sea-level rise, flooding from such events could occur more frequently. An initial assessment of overtopping conditions and flood extents suggests that with similar swell wave conditions and sea-level rise, associated with 2°C, Hulhumalé would be safe from flooding. However, rises greater than 1m (plausible by the end of the 21st century with warming greater than 4°C) could result in more frequent flooding unless adaptation is undertaken.

References

- Photographs by Laurens Speelman and Sally Brown. Please do not reproduce without permission.

- Hindcast data was extracted from WaveWatchIII: http://polar.ncep.noaa.gov/waves/ensemble/download.shtml

Author:

Sally Brown

University of Southampton (SOTON), United KingdomMatthew Wadey

University of Southampton (SOTON), United KingdomRobert J Nicholls

University of Southampton (SOTON), United KingdomAli Shareef

(Ministry of Environment and Energy, Government of the Maldives,Maldives)

Zammath Khaleel

(Ministry of Environment and Energy, Government of the Maldives,Maldives)

Jochen Hinkel

(Global Climate Forum, Germany)Daniel Lincke

(Global Climate Forum, Germany)